Walking Into Angola’s Past: Inside the Slavery Museum That Honors Pain, Memory, and Resistance

Fundacion Rapala – On the edge of Luanda, a small white house tells a huge story. This building, now the National Angola’s Museum of Slavery, once belonged to Álvaro de Carvalho Matoso, a powerful Portuguese slave trader. Many visitors come here to understand how deeply the Atlantic slave trade shaped Angola and the world. Between the 1400s and 1867, at least 12.5 million Africans were enslaved. Nearly half came from the region around modern Angola. More than 1.6 million people were taken from Luanda alone, most of them sent to Brazil and the early American colonies. Today, descendants of enslaved people return to this site to reconnect with their past and search for pieces of their family history.

A Chapel Where Identities Were Taken

One of the most striking rooms in the museum is a former Catholic chapel. Here, enslaved Angolans were baptized before they were forced onto ships. The Portuguese used this ritual to erase names and identities. According to researcher Marlene Ananias Rodrigues Pedro, enslaved people received new Portuguese names that replaced their real ones. Many later used “Angola” as a surname to show where they came from. Standing inside the small chapel today, visitors feel how painful this loss must have been. The wooden cross and baptismal font still sit in the room, offering a reminder of how spiritual symbols once served a violent purpose.

“Read More : How People Can Shape Global Politics Through Game Theory and Civic Power”

Tools That Show the Cruelty of the Trade

A nearby room displays objects that reveal the brutality of the slave trade. Manacles, chains, guns, and drawings line the walls. One image shows slavers striking people with paddles covered in nails. Another shows white families feeding Black children scraps under a table, while adults stand behind them with metal collars around their necks. Two large metal stills sit outside on a balcony. Slavers used alcohol to weaken captives before loading them onto ships. The tools and drawings make the cruelty of this period impossible to ignore.

A Museum That Also Tells a Story of Resistance

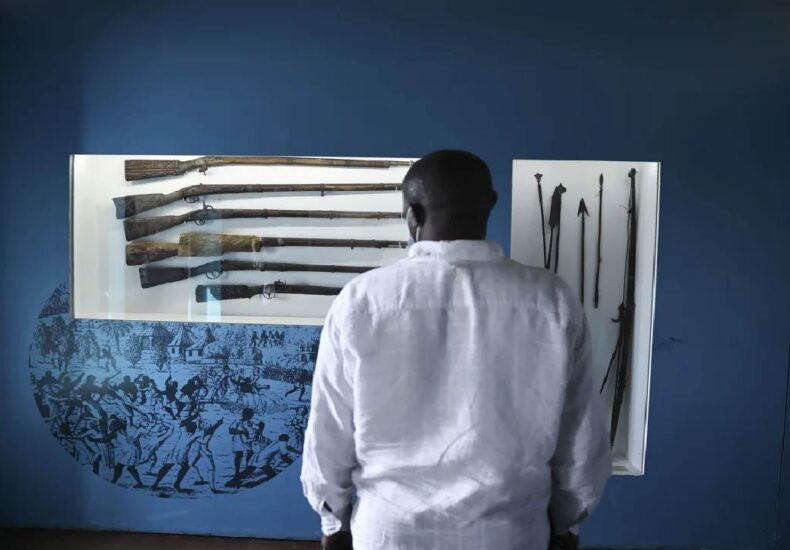

Unlike many slavery museums, Angola’s museum does more than show suffering. It also highlights centuries of resistance. One gallery displays poison arrows, muskets, and handmade weapons used by Angolans who fought back. Pedro notes that freedom in Angola never came easily. People resisted both slavery and colonial rule for generations. Their efforts continued into the Angolan War of Independence from 1961 to 1974. Angola finally gained independence in 1975. This part of the museum reminds visitors that enslaved people were not only victims but also fighters and leaders.

A New Mission: Rebuilding Lineage and Memory

Today, the museum is taking on a new role. Director José António Fazenda and his team are working to digitize Luanda’s historical archives. They hope to build a library where visitors can search for records linked to enslaved ancestors. These archives list ships, dates, and destinations. Although they rarely list African names, they still hold clues that may reconnect families with their origins. This project aims to turn the museum into a place of healing and research, not just remembrance.

Saving Fragile Records for Future Generations

Many of the historical documents still sit in Luanda’s National Archives. Access is limited, and the storage conditions are far from ideal. The museum team wants to change that. They are collecting materials, scanning old pages, and building a safer digital system. These records reveal routes, movements, and resistance efforts that have been overlooked for centuries. By preserving them, the museum hopes to help future generations understand both the trauma and the strength of the Angolan people.